Since 2008, I’ve been creating a photographic archive depicting America’s rich trove of wild edible flora. The project has taken me to fifteen different states, so far, and I’ve amassed a collection of over one hundred and forty specimens. The work sprung from disillusionment with the position of landscape photography in relation to pressing threats like climate change, extinction, pollution and the loss of commons. Too often, the genre traffics in the aesthetics of nature instead of the inner workings of ecology. To address climate change and environmental degradation, I felt a radically different artistic strategy was necessary. The resulting series; J.W. Fike’s Photographic Survey of the Wild Edible Botanicals of the North American Continent; Plates in Which the Edible Parts of the Specimen have been Illustrated in Color seemed a promising vein of work that satisfied the new critical criteria I set for landscape-based artwork – a socially engaged approach that was accessible without sacrificing theoretical depth and possessed the potential to create change.

By employing a system that makes it easy to identify both the plant and its edible parts, the images function as reliable guides for foraging. Joseph Beuys’s thoughts on social sculpture challenged me for years and eventually lead me to explore ways of adding utility and a broader type of engagement to photo-based artwork. This concrete, functional aspect of the project directs viewers to free food that can be used for sustenance, or as raw material for creative economies. The seemingly objective style of the images references early contact prints from the dawn of photography (Henry Fox Talbot, Anna Atkins) when photography’s verisimilitude proved a promising form of scientific illustration for taxonomical undertakings. Anna Atkins is credited with publishing the first photography book, Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions in 1843, filled with contact prints of algae seemingly floating in the blues of deep water.

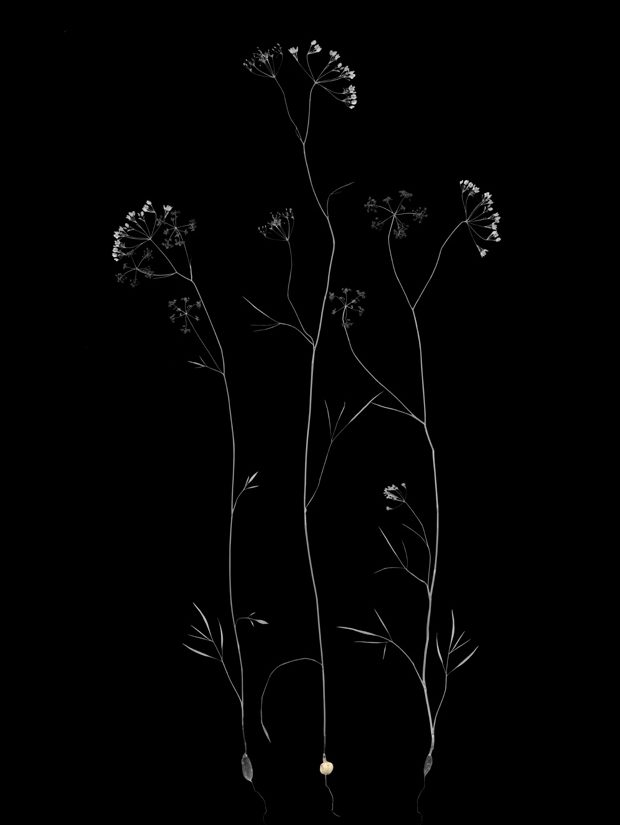

Beyond functionality, I try to construct images that operate on multiple levels theoretically and perceptually. Upon longer viewing the botanicals begin to transcend the initial appearance of scientific illustration – they writhe and pulsate trying to communicate with you about their edible parts while hovering over an infinite black expanse. This opticality becomes a physiological parallel to the chemical effects of ingesting the plants and opens up a mystical space for contemplation, communion and meditation. The scientific yields to something potentially spiritual as the viewer begins to experience our symbiotic evolution with the plant kingdom. I’ve been informed and inspired by Buddhist and Native American teachings about ecology, interconnectivity, and consciousness. I found the Buddhist teaching on dependent origination particularly profound and elegant: “If this exists, that exists; if this ceases to exist, that also ceases to exist.” I often find myself marveling at the intricate web of overlapping systems and sheer length of time – incomprehensible fathoms – it took to establish this symbiosis.

To achieve this layered aesthetic the plant photographs are meticulously constructed. I photograph multiple specimens of the same plant and combine the best elements from each to create an archetypal rendering of the species. By judiciously rearranging, scaling, and warping I can vivify the plant and turn the ground into space. This subtle reference to shamanic scrying and other mystical forms of seeing nudges the work towards the numinous. I hope viewers carry this numinous experience back out into the landscape, into their communities and see the plants that surround them in a fresh, wonder-filled way. Or, as Ralph Waldo Emerson more eloquently described the phenomenon, “The greatest delight which the fields and woods minister, is the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable. I am not alone and unacknowledged. They nod to me, and I to them.”

Since my early years, I’ve been enamored with stories of adventures and epic quests based in the American landscape. My grandmother would recount tales for hours in her sweet, lively southern drawl, like our relative Sergeant Pryor’s experiences on the Lewis and Clark expedition, or how we were related to Pocahontas by marriage – stories that captivated my boyish imagination, and sparked a desire for adventure. Later in my life, the artwork of William Bartram and John James Audubon rekindled these fantastical notions. In some ways, my epic project is a modern-day attempt to capture some of the spirit of these earlier eras when art, science, journey and discovery seemed more possible. The prolix name of the series harkens back to title pages often used in manuscripts from the 18th and 19th centuries (Edward Curtis’s 1907, The North American Indian Being a Series of Volumes Picturing and Describing The Indians of the United States and Canada Written Edited and Published by William S. Curtis, for example).

The plants too, often tell fascinating stories, and this aspect of the fieldwork is quite educational. Through the process of slowly wandering through fields and forests with used guidebooks one learns great history lessons: how Native Americans traditionally prepared and utilized the plant, how settlers brought seeds from European plants that quickly spread with the winds and other quirky bits of folklore. One such anecdote recounted how Native Americans called plantain “white man’s footprint” because everywhere white men walked the plant seemed to spring from the imprint, or how battles were fought between tribes over patches of yampah – a delicate plant with a delicious corm that grows in mountainous areas of the Southwest. Such narratives have the potential to weave people into their locations in rich, powerful ways.

This work offers a dose of something palliative for the ills of alienation – a sense of connection to a certain place, a certain ecosystem, a type of belonging. With this in mind, I plan on continuing the survey until I’ve amassed an expansive enough cross-section of the botanical life on the continent to mount biome-specific exhibitions anywhere within the continental United States. After ten years of work, I’m excited to be approaching this goal. I hope the photographic survey can serve as a historical archive of botanical life during eras of extreme change, and provide viewers all over the country an opportunity to feel the type of bond with their landscapes that will encourage health, engender wonder, help identify free food, and most importantly, inspire greater concern for environmental issues.

(Top image: California Poppy, 36″x30″, 2015.)

______________________________

Jimmy Fike was born on a cold December morning in Birmingham, Alabama. He received a BA in Art from Auburn University and earned an MFA in Photography from the Cranbrook Academy of Art under the tutelage of Carl Toth. Jim has taught art at Wake Forest and Ohio Universities and is currently an Art Faculty Member at Estrella Mountain College in Avondale, Arizona. His photographic work endeavors to find creative, contemporary ways to approach landscape by incorporating place, identity, ecology, and mythology. His series on wild edible plants has been exhibited in a number of shows across the county, featured in the L.A. Times, and can be found in the permanent collection of the George Eastman House Museum. When not creating art or teaching, Jim enjoys reading, cooking, picking guitar, and hiking with his dogs Sallie and Scrappy Doo.

Inspiring article covering a fantastic ecological photographic journey – thank you for sharing as an artist working in Scotland who is trying hard to still seethe beauty of marine algae through the entangled plastic pollution . I will try harder to keep the natural forms in view! http://www.littoralartproject.com